In 19xx I was a very bored middle school student who really only looked forward to two parts of my day; social studies class and student newspaper. This end of day elective was my first real exposure to article and content writing and I still remember our teacher/editor always reminding us that research and investigating should always answer six very important questions; where, what, when, who, why, and of course how.

If you are a person who is interested in tracking down physical manifestations of history, you’re constantly asking yourself where, when, and even what. But have you ever stopped to consider HOW the markers you’ve found got there? Or WHO got to decide on what events are commemorated and which aren’t? Or even WHY people decided that markers were something that needed to be placed?

Turns out that depending on where you are, these kinds of questions come with some very different and complex answers, and some of those answers are even more interesting than the markers themselves.

Knowledge Quiz

In my pursuit of better understanding these questions, I actually uncovered some interesting facts about markers and landmarks. If you’re interested, you can take this short quiz below to test your “Marker Mastery” and see how much you know! Answers are at the bottom of the post!

- What was the first landmark entered into the National Register of Historic Landmarks?

- What is widely considered to be the oldest surviving historic landmark?

- What property/building was the first ever purchased by the government for historic reasons?

- What state has the smallest number of landmarks in its state index?

- According to the HMDB, what state has the most landmarks?

- What commemorative marker is considered to be the oldest?

As is evidenced by the facts in the previous quiz, marking locations of significance has been going on since time immemorial. Indigenous peoples were among the first to do this in North America and did so in many different ways such as effigy mounds, stone medicine wheels, petroglyphs, and totem poles. These early markers were created to mark places of historic, cultural, or spiritual significance and to tell stories that were key to their cultures.

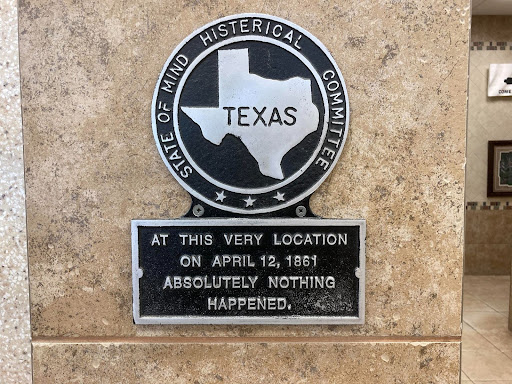

The definition of what is significant has “expanded” a bit over the years…

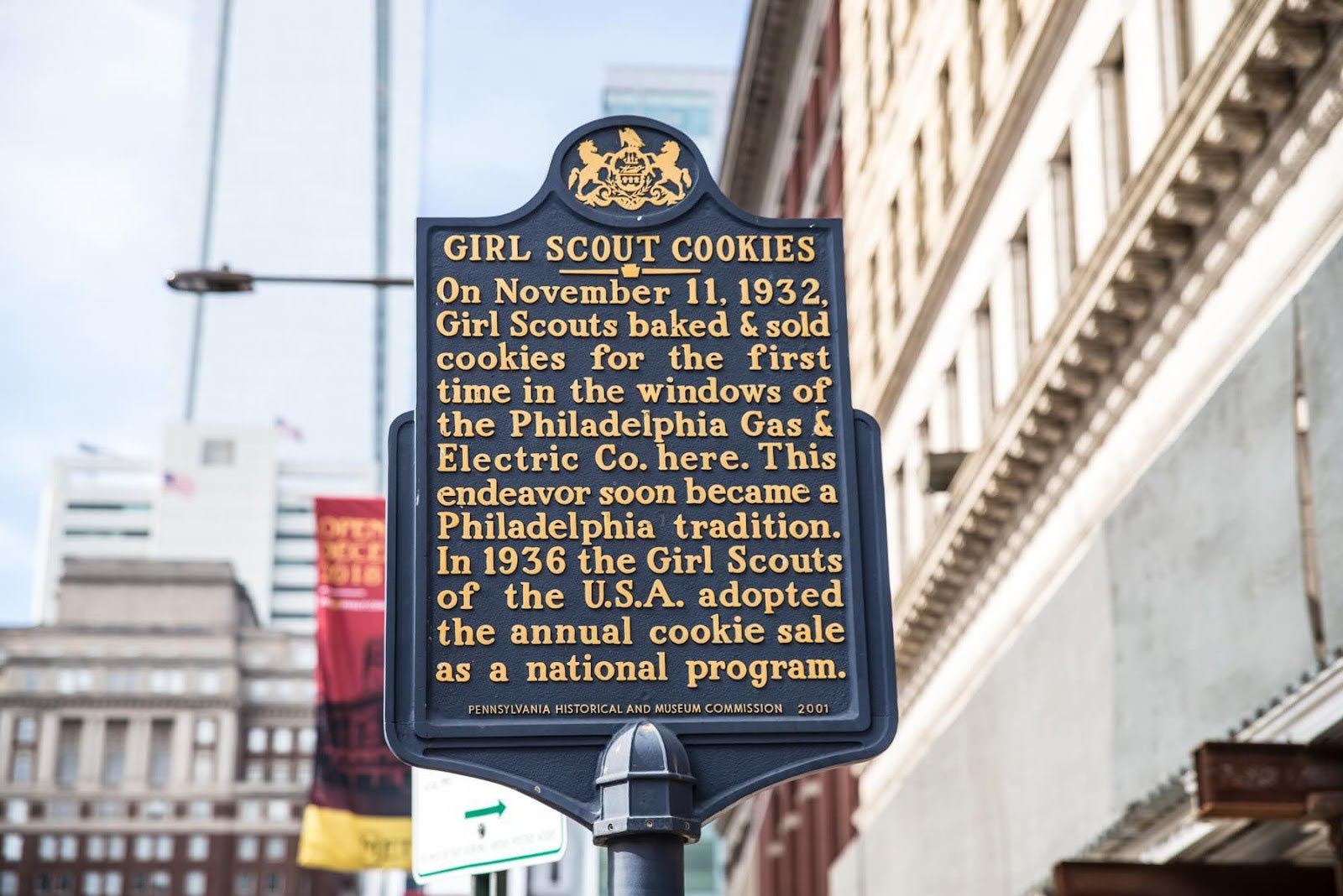

Today, the human quest to denote places of import related to our shared human experience continues as evidenced by the more than 242,000+ markers catalogued in the HMDB and the collection of 240,000+ that are accessible through the ExploreHere app.

The markers in these archives are scattered throughout the country and represent a patchwork effort by a vast collection of individuals, societies, and government agencies, all of whom had their own motivations and reasons, which makes telling the story of how they all came to be in a single article more or less impossible.

WHAT - A Model Landmark Program

For the purposes of this article, I am focusing most of my attention on California's Historic Landmarks Program managed largely by the state’s Office of Historic Preservation. I did so for a number of different reasons listed below;

- They are transparent. They have a well established and maintained program managed by multiple agencies with lots of easy-to-access resources about how the program is run that encourages participation from the public.

- They are representative. In addition to the official list, they also have many markers and landmarks that predate the official criteria that illustrate how programs like theirs have evolved over the centuries in ways that mirror national trends or those in other states.

- They are responsible. They have a strong and ongoing effort regarding reassessment and updating the official list to ensure historic accuracy and inclusive view points.

Outside of these reasons I am also a former state park docent who has done archival research on many of these locations including proposing one for inclusion among the official list. I also started a quest to visit every single landmark in the state which I abandoned about halfway through when I realized just how Herculean an effort it would require to visit all 1044.

WHY - The Beginnings Desire for Preservation and Protection

While historic preservation efforts in California had begun as early as the 1850’s, California's landmark program began thanks to the efforts of one concerned citizen, a pattern that is similar to those in other states and cities. In 1895, Charles Lummis established the Los Angeles based Landmarks Club. Lummis was a bit of a character whose biography reads like the plot for an HBO biopic; he was a classmate of Theodore Roosevelt who published poetry about his love of smoking. While living in Ohio he was offered a job by the Los Angeles Times and while walking there for his job he crossed paths with the famed outlaw Frank James. Once in LA he became an early advocate for indigenous rights, helped authors like Jack London and John Muir gain notoriety by publishing some of the early writings, and survived an assasination attempt while living among the Pueblo people of New Mexico. And that’s not even half of what I learned about him, but most relevant to this article was how he used his positionality as a newspaper man to become a powerful voice for historic preservation.

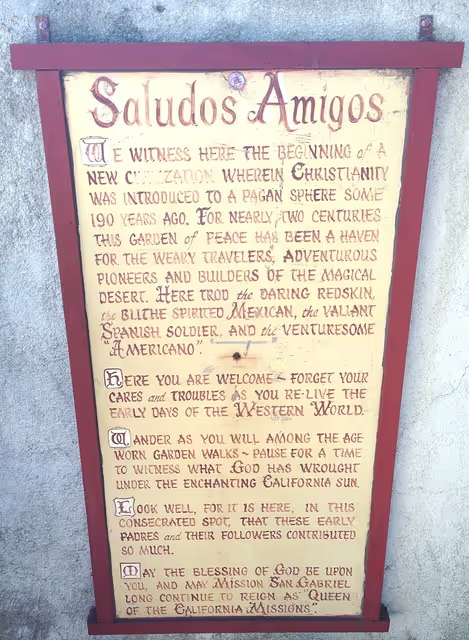

Lummis had noticed that most of California’s historic missions, churches built by the Spanish that were both significant and tragic parts of the state's history, were falling into disrepair. “In ten years from now, unless our intelligence shall awaken at once, there will remain of these noble piles nothing” he wrote. The Landmark Club then set to work promoting these sites by creating physical markers and maps while advocating for their preservation.

This story, of concerned citizens seeing the need for preservation, was the why that led to the establishment of many other programs such as Landmarks Illinois in 1971 which was formed in response to the demolition of a historic building in Chicago or Indiana Landmarks which was founded by pharmaceutical magnate Eli Lilly to protect notable buildings and locations.

WHO - Many Organizations, One Shared Goal, No Shared Criteria

Lummis efforts were noticed in other parts of the state and were soon being duplicated by a wide variety of people and organizations who also sought to document “where history happened” in California. In 1902 The Native Sons of the Golden West, an organization that sought to preserve history but as the name suggests only one very specific (and very white) narrative began their own effort to place markers. On their heels was The California State Automobile Association who sought to physically document history as a way of encouraging travel and commerce. Their efforts included the installation of mission bells along the El Camino Real and many markers related to the mission period that helped spark the romanticization of Spanish California much to the chagrin of the indigenous communities who now had to see more and more physical manifestations of historic trauma.

And then there was my absolute favorite historical society E Clampus Vitas, which can only be described as what would be born if a historian and a frat bro had a baby. The history of this organization is so shrouded in myth and folklore that even the different chapters disagree about their origins, but they placed many of the states oldest markers and were responsible for perpetrating the Sir Francis Drake Historic Plate hoax which still stands as the absolute best marker-related prank of all time.

All of these organizations added to the slowly growing collection of mis-matched markers that was steadily adding up across the state and led to the growing call for some sort of standardization since the historical authenticity of many of these early markers were questionable at best. An example of this would be Frog Woman Rock. Designated as state landmark #549 in 1956, the rock’s original name was problematic as it was a derogatory slur for indigenous women that we’ll refrain from typing and its inclusion in the registry was based largely on a highly questionable tale that was widely regarded as folklore rather than history. There was little required documentation and as the centennial approached, it was determined time for the golden state to get its house in order.

In 1931 the state of California decided that it was time to establish a formal process, criteria, and a governing advisory body which led to the creation of the California Historic Commission. This was followed by the addition of an advisory committee in 1949 and eventually a more detailed and standardized process that was solidified by 1970 and is more or less the one used today.

HOW - The Nomination Process

The process for creating landmarks as it exits today involves the following steps;

- A location is nominated and an application is filled out and submitted that includes documentation and historic background to demonstrate that it meets the state's criteria.

- The application is reviewed by OHP staff and then goes to the advising committee which meets periodically to decide which to add and which to reject.

- If approved, the director of California State Parks must sign off and presto - there is a new landmark!

One of the things that is most interesting about the process is that anyone can nominate a place for inclusion on the official list, even people from outside the state! So if you’ve ever had a desire to not just locate markers, but also create your own, you can! And this opportunity isn’t unique to California, as many states such as Colorado and Texas and cities like New York have processes to nominate new landmarks. Even the National Registry of Historic Places will accept nominations from the public. And once your nomination goes through the process and is approved, they even have instructions for how to go about getting a plaque installed to commemorate it along with a list of vendors! Most states have a standardized format for their markers today so the dimensions are clearly spelled out.

Features like these provide opportunities for more public participation, an important feature of a strong marker program as it democratizes the designation of what is history and the stories that are told. This in turn creates more public buy-in and support that leads to more diverse representation and, ultimately, a more complete historic record spelled out in the markers we see across our landscapes.

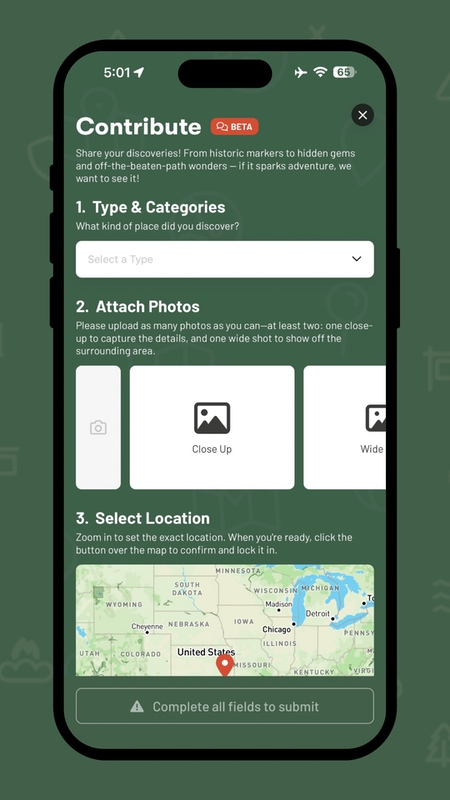

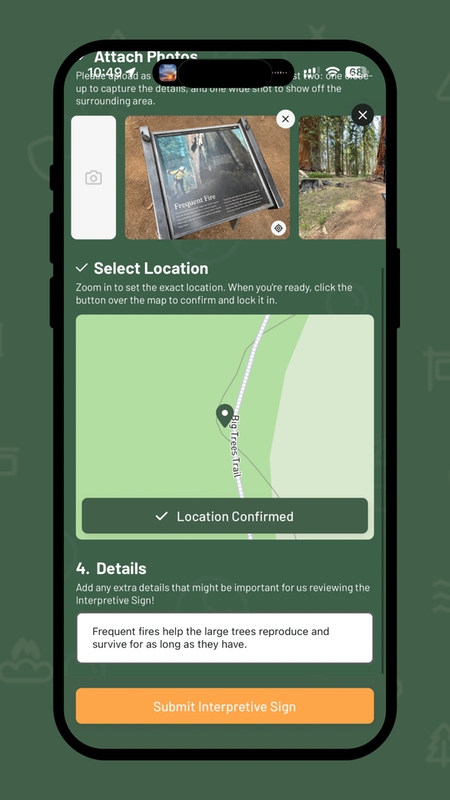

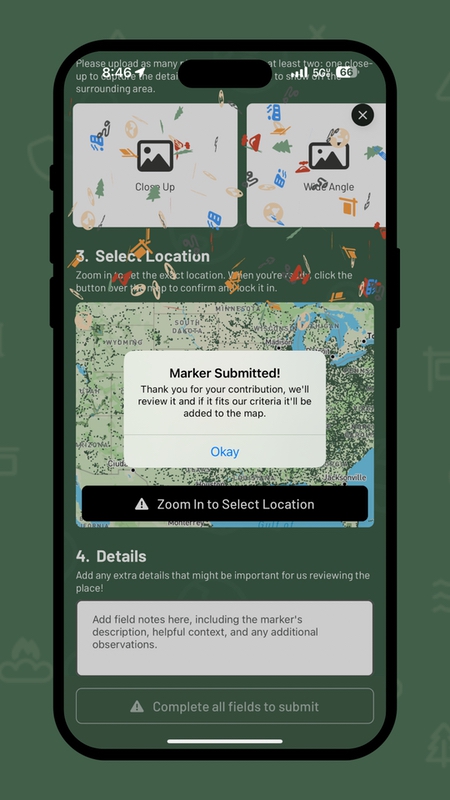

And if you’re reading this, it means you’ve already got access to a great way to help grow this public record through the new Contribute tool in the ExploreHere app! Just click on the icon, document what you’ve found by completing the required fields in the app, and submit it to the ExploreHere team for review!

So the next time you are out on the road, don’t just look for the historic places and spaces that are already marked, pay attention to the ones that aren’t. They might be waiting for someone like you to create the next entry in your community's landmark registry.

The author would like to thank the California OHP for their help with this article.

Quiz Answers

- Serpent Mound, OH

- 1774 Inscription on Plymouth Rock

- Independence Hall, PA

- North Dakota with 7

- New York

- The Elijah Clarke Monument in Georgia - 1825

Sources

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ch.2014.91.1.43?read-now=1&seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents